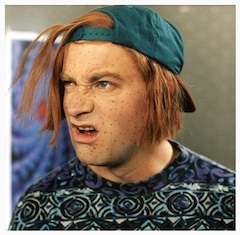

“Nyah”

For years, Google has been the Stroppy Teenager Kevin when it comes to copyright – full of attitude, and refusing to tidy up the bedroom. But do yesterday’s concessions make any difference?

No.

The way Google has handled this won’t inspire confidence that it’s sincere in finding a long-term solution. The commitments are vague and the headline-grabber – the DMCA response – merely obliges Google to do what it’s obliged to do anyway.

Google has already tipped its freetard supporters overboard once this year by abandoning its Net Neutrality posturing and lobbying for something more practical – a rapprochement with Verizon it hopes will be a template agreement. As news of Google’s new copyright statement rippled round the web, people wondered if it had repeated the trick. But the substance doesn’t really match the billing.

It’s worth identifying the beef. Thanks to digital technology, informal copyright infringement is always going to take place. When it’s word of mouth, it’s almost impossible to monitor and police. The hardcore freetards will always be with us – just as people who never buy a round of drinks in a pub will always be with us.

It’s also a fair bet that more infringement will take place through such subterranean channels in the future than it does today. Possibly much more. Creative industries will just have to live with it, just as they learned to live with home taping.

But this really isn’t the issue here. The issue for creatives, many of whom are small independent operators, is when giant middlemen such as Google encourage piracy and profit from it, while using the law as a shield. Remember that by law, we’re all creators, and automatically protected by the umbrella of international frameworks that recognise and encourage creativity. (For some creative works you have to assert some of your rights, such as moral rights, explicitly – but most are covered automatically.)< Creators' rights are human rights. But all this protection is useless if the giant scrapers, aggregators and middlemen of the Web play deaf. The plight of filmmaker Ellen Seidler has gone a long way to highlight this, bringing the issue home in ways that professional lobbyists haven't managed. Nobody could mistake Seidler for a pigopolist. Yet her hit independent lesbian romantic comedy And Then Came Lola led to Seidler spending much of her free time manually filling out infringement notices, and it was almost certainly deprived of a DVD release by pirates.

The DMCA is supposed to redress the balance by helping the individual creator – who doesn’t need a lawyer. But Google hates it, and warns people off using it.

Here’s an example [1] of how Google scares an individual away from exercising their rights. If you dare fill out the DMCA, you get a super-scary warning that:

Your letter may be sent to a third party partner for publication and annotation … your letter may be forwarded to the Chilling Effects for publication …

This implies you’ll be identified and humiliated, and hauled before a cyber court of bullying freetards, simply for exercising your rights. Bullying was enough to silence Lily Allen – so what chance do you have? Are you feeling lucky?

Then Google warns you of the possible costs involved – a case in which the party making the request was hit for $100,000. Yet the DMCA requires no lawyer, by design. The warnings do the trick – and scare most people away. And it’s still up there [2], intact.

Google has promised to act on DMCA requests within 24 hours. But everyone already has to act on DMCA requests immediately. So why this is regarded as a “concession” is a puzzle.

Google actively tidies up its own search results, but pretends to be selectively unable to do so when rightsholders knock on the door. Nyah, it tells photographers, publishers, songwriters, filmmakers and bands. Just like Kevin can go selectively deaf when asked to tidy his bedroom. Nyah. At least it has acknowledged the double standard here, implicitly if not explicitly.

Sarah Hunter, former Blairite culture policy advisor, god-daughter of Lord Irvine and now Head of UK Public Policy at Google, gave a decent impression of Kevin The Teenager to a Westminster conference I had the pleasure of moderating recently. Hunter’s contribution was a collection of Noughties-era anti-business, anti-creativity prejudices.

Hunter said she couldn’t see why we all had to call creative industries “creative” – shopping was just as important to UK plc. She gave every impression of having scribbled her talk down on an envelope in five minutes – and it stunned the room with its arrogance, complacency and philistinism.

A month ago, we gather, Hunter was mauled in private by Ed Vaizey for not doing more to help small creative music businesses. (The talk mauled everyone – music business and ISPs – for not doing more – but by reminding Google that it has to respect other established UK businesses, Vaizey surprised everyone.)

For lifelong policy wonks like Hunter, who’ve never really had a proper job in the real world, this must have come as a shock. For Google, they must be wondering if Hunter is now an asset, or a liability.

For some reason, internet utopians still regard Google as the heroic leader in the struggle against The Man – and it let its fans do the talking on the blog post yesterday.

“I think the ‘entertainment’ industry just needs to realize no one wants to pay their outrageous prices for stuff,” writes one freetard. “I don’t think copyright has long to live and it will rapidly become irrelevant as internet speeds improve,” writes another.

As Kevin The Teenager might say – “whateverrrr…”.

0 responses to “Nyah! Google is the Kevin the Teenager”