At Christmas, charities launch their most emotive appeals. After almost two years of seeing their fundraising crippled by lockdowns and social distancing, they are more needy than ever. But I would think carefully before responding to one particularly aggressive annual solicitation.

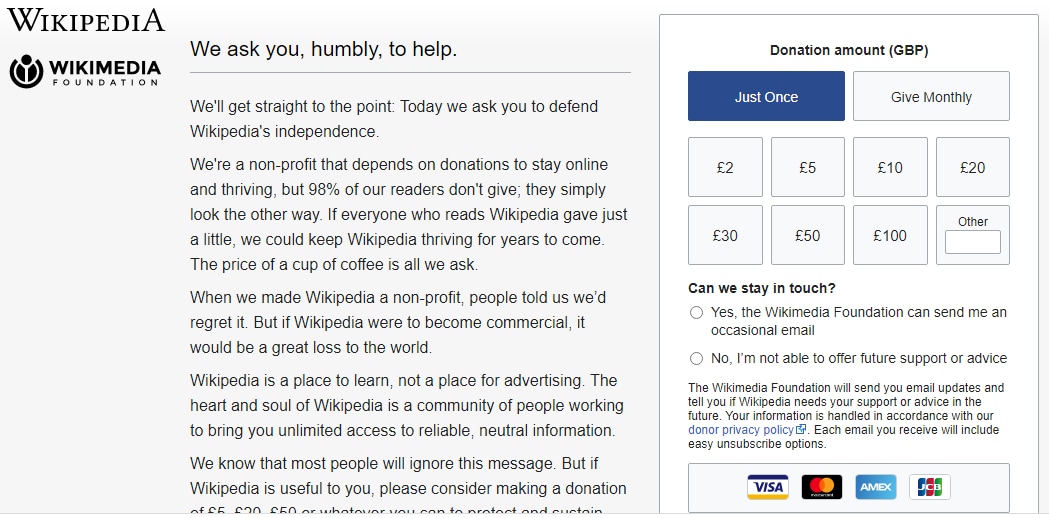

Throughout December, Wikipedia is demanding a donation from visitors to the site. “Please don’t scroll past this,” my iPhone begs me. This is apparently needed “to protect Wikipedia’s independence”. The banner ads pose an existential issue: the website that so many people find so useful is in peril, and may even disappear if the funding drive falls short. But this is suspect.

The Californian corporate entity behind the annual appeal is called the Wikimedia Foundation, or WMF, and while it holds certain intellectual property intangibles – largely the name and the brand – you may be surprised where your donation really goes.

It doesn’t go to pay someone beavering away on the site itself, because the content is created and curated not by the WMF, but by thousands of volunteers who work for free.

The Foundation enjoys an uneasy and sometimes antagonistic relationship with its editors and contributors. To give you some idea of how testy this can be, when the Foundation proposed changing its name to the ‘Wikipedia Foundation’, the volunteers rebelled, and some of them even described it as a slur.

We know that the last-ditch appeal to ‘protect’ or ‘support’ Wikipedia’s independence is dubious, because very quietly last week, the WMF released its audited accounts for 2020-2021.

The WMF holds assets of $240m (£181m), which is an impressive increase of $49m from a year ago. A total $208m is held in cash and short-term assets which the foundation can use to pay any unexpected bill – making any notion of the emergency that the ads imply today quite preposterous.

But doesn’t a global information operation cost a lot to run, even if the content creators work for free? In fact, it costs much less than you might think, and just a tiny fraction of the riches that WMF has at its disposal.

In 2013, WMF’s then vice president of engineering and development and its deputy director, Erik Möller, calculated that the Foundation could be sustainable on “$10M+ a year”. This went well beyond what was needed for “bare survival”, Möller explained, and would comfortably cover hosting, new equipment and back office fees like legal expenses.

The Wikipedia donation banner we see today insists that “the price of a cup of coffee is all we need”. But it doesn’t “need” it at all.

Indeed, the WMF also has over $100m on top of that in the form of an endowment (it reached the nine-figure target some five years early). So based on Möller’s inside knowledge, and allowing for inflation, we would not need to see another begging banner on Wikipedia for 20 years.

How much is enough, then? Naturally it wants more. The WMF’s principal programme manager, Guillaume Paumier, recently allowed himself to speculate that $1bn a year might not be an outrageous target.

It has been fascinating to watch the WMF professionalise over the past decade, and begin to mirror some of the grotesque behaviour that discredits the NGO and charity sectors. The WMF has ballooned from a half a dozen staff to over 500, with many on six-figure salaries.

WMF’s 2020/21 accounts show revenue has swollen to $163m. And some of the recipients may not meet with universal approval. Two years ago, the foundation created something called a ‘Knowledge Equity Fund’. This fund would be distributed to third parties which support “shifting away from Eurocentricity, white-male-imperialist-patriarchal supremacy, superiority, power and privilege”.

To see how this might be achieved, it advised us to read a document called “Woke to Work”. Wikipedians only found out about the fund when it appeared as a line item in the accounts.

“The sense of entitlement that comes from people who know they can raise money easily from Wikipedia is astonishing, and they don’t even feel they have to justify themselves,” one insider tells me. “They’re woke people. They’ll use it correctly – it’s for a good purpose. They’re morally superior.”

One of the most tantalising questions in media is what may happen next. Wikipedia’s content is ubiquitous: even if you never visit the site, Wiki factoids will be directed at you even from your smartphone or Alexa speakers. That’s a lot of power.

So imagine if some of that $300m war chest was used to pay content creators. It would begin to attract professional researchers and editors – and some veterans would no doubt object to their personal fiefdoms being invaded.

Then again, what if as in some modern day Marxist fable, the unpaid proletariat of Wikipedia rebelled against this exploitative new bourgeoisie, and ‘forked’ the project, starting on day one with an identical clone? That’s perfectly feasible, given the licensing, and there’s little love lost already. The WMF would be left high and dry.

One wonders how desperate the “don’t walk away” appeals must be before complaints are lodged. Whether it’s children, veterans or unloved animals – they all deserve your £2 more than Greedimedia.

This column first appeared at The Daily Telegraph.

0 responses to “The unquenchable greed of Wikipedia”