A Texan family has been handed a harsh lesson in what the Creative Commons “movement” really means for creatives who use its licences.

Filmmaker Damon Chang uploaded a family photograph of his young niece Alison to Flickr, only to discover weeks later that it was being used by Virgin Mobile in an expensive advertising campaign. Neither Alison Chang nor her youth counsellor Justin Wong, who took the photograph, have received compensation for the use of the image – having handed over the rights without realising it. Damon Chang used a licence which permits commercial reuse – and even derivative works to be made – without payment or permission of the photographer: Merely a credit will do to satisfy the terms of the licence.

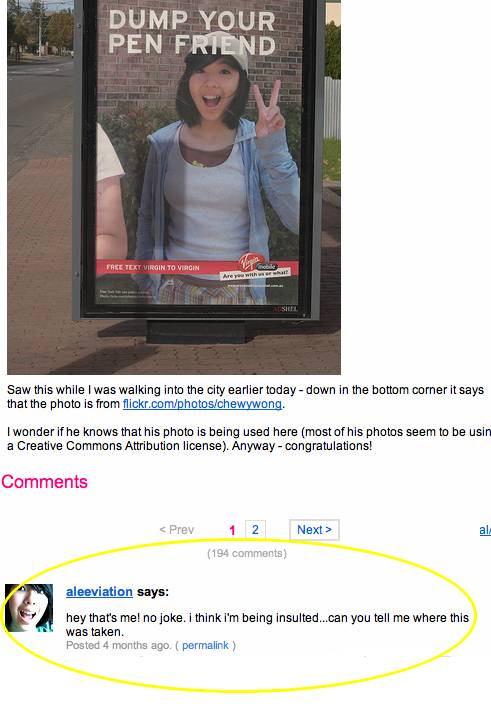

Both Changs believe the use of the photograph was insulting and demeaning, as Alison – a minor – became known as the “dump your pen friend girl”. And after taking legal advice, the Chang family is now suing Virgin Mobile USA and the Creative Common Corporation.

Virgin hoovered up over 100 “user generated” images for its ad campaign – saving itself a fortune. The lawsuit accuses Virgin of invasion of privacy, libel and breach of contract, but it’s the section of the lawsuit that names and shames Creative Commons that promises to have lasting consequences for “Web 2.0” and “user generated content”.

“Creative Commons owned a duty to Justin Wong,” argue the Chang family in the complaint, but “breached this duty by failing, among other things, to adequately educate and warn him… of the meaning of commercial use and the ramifications and effects of entering into a licence allowing such use.”

Virgin had said it believes “…the spirit of the Creative Commons agreement matches Virgin’s philosophy.”

(A philosophy of getting stuff for free, is presumably what they mean.)

In fact, in all but one detail, this is the “Creative Commons” working exactly as it should: Making it easier for images to be re-used, without permission or compensation to the creator. In the parallel economy of “Web 2.0”, sharecropping is the norm. Virgin goofed in only one respect – by failing to credit Justin Wong, which it could have done so in tiny print. Otherwise, it got the free ride it wanted, thanks to the Creative Commons.

In this enthralling thread on Flickr (spare five minutes if you can to read it) – Alison discovers, to her horror, that she’s famous – and lawyers rally round to help. Here’s how it starts:

Alison Chang discovers how her image has been used. Surely a defining moment in the history of “user generated content”?

Alison’s brother Damon explains his motivation at length in this message, further down the page.

“People allowing commercial usage of their photography on Flickr are suckers being taken advantage of,” is the advice from one of several professionals who pitched in.

“With all the money [Virgin Mobile] saved on photography through this campaign, they will probably break even on fees for the attorneys they keep on regular retainer anyway.”

Flattering to deceive

For long-time watchers of Creative Commons, it’s simply the latest in a series of confusions and misunderstandings that leave creators a dollar short.

In fact, the “movement” itself is founded on a fiction – that somehow, the era of free movement of cultural goods is coming to an end, requiring a new set of legal mechanisms.

(Out in the real world, where thanks to broadband we can consume digitised versions of cultural products without paying a penny for them for the rest of our lives – with a negligible chance of getting nicked – the idea of a clampdown is laughable. If this is oppression, many of you are probably thinking, can we have more please? But without this fiction, the rest of the Commons edifice would have no reason to exist: it would be a legal conceit with nowhere to go.)

Few participants who slap a CC license on their work understand that the mechanism was designed to benefit the network, not the humans, by removing “frictions” such as compensation or consent.

Meanwhile, confusion abounds – and we don’t just mean the bewildering farrago of licensing permutations.

After criticism that the foundation-backed non-profit appeared to offer something it didn’t – legal backup – the Commons produced a “you’re on your own – don’t call us” disclaimer.

Then there’s what to do if you change your mind. You can’t. After we drew attention to this two years ago, even some prominent Creative Commons evangelists – and as a pseudo-religious cult with its own Messiah, it has a fair few of these numpties – were surprised to learn this.

(For example, a songwriter who’d put out a tune under a CC license discovered he’d given away his rights, lock stock and barrel – and couldn’t do anything about it.)

A Commons licence promises freedom, but requires the creator to abandon several; including the freedom to assign one’s rights as one wishes, according to principle or whim.

While the Changs have now ditched the CC licence for a more sensible “All Rights Reserved”, they’ve only been able to do so because of Virgin’s failure to attribute the photographer, and it’s far from clear that their change might stick.

Earlier this year, marketing consultant Seth Godin used a similar licence the Changs had used for a freebie booklet he’d written , only to discover it was printed up and sold for profit without his knowledge, with no compensation. He couldn’t revoke anything, because no terms had been breached.

Is there a better way?

Evangelists have reacted in time-honoured fashion – by blaming the user. Just as Wikipedians blame the user for absorbing incorrect information, and OpenOffice nuts blame the user for not fixing bugs they discover, Commonistas today have rounded on the poster for… posting the photograph to the internets. A bit rich, you might think, coming from the “sharing” community.

Of course copyright, particularly in the European context, affords the little guy plenty of protection and some unique advantages over would-be exploiters.

If the photograph had been released under conventional “All Rights Reserved” terms, then Virgin would have been obliged to check with the family first – and also throw some of its multi-million budget advertising budget to the 100+ photographers who made the campaign so memorable. And by taking advantage of moral copyright, or “droit d’auteur”, you can oblige a tacky commercial opportunist to withdraw the work with one just phone call.

No wonder Commons licence evangelists hate to tell the truth about copyright: The truth is that the world has always ticked along just fine without them.

What are the chances the Commons will add a disclaimer:

"Using this licence may invade your privacy, and seriously damage your wealth"?

0 responses to “Creative Commons sued for deception”