The idea that seized the imaginations of the bien pensant chattering classes in the Noughties – “Peak Oil” – is no longer relevant. So says the commodities team at Citigroup, and policy-makers would be wise to examine the trends they’ve identified.

“Peak Oil” is the point at which the production of conventional crude oil begins an irreversible decline. The effect of this, some say, is that scarcity-induced prices rises would require huge changes in modern industrial societies. For some, Peak Oil was the call of Mother Earth herself, requiring a return to pre-industrial lifestyles. One example of this response is the “Transition Towns” network, a middle-class phenomenon in commuter belt towns in the UK.

But in a must-read research note [PDF] issued this month (which is also implicitly critical of the industry) this is premature.

Thanks to “unconventional” oil and gas, which can be tapped thanks to technological advances, Peak Oil is dead.

The analysts write:

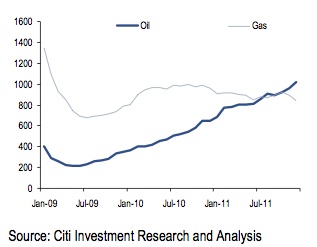

The belief that global oil production has peaked, or is on the cusp of doing so, has helped to fuel oil’s more than decade-long rally. The resurgence of US gas production to well over its 1970s peak and into the number one slot globally over the last seven years is a result of hydraulic fracturing – fracking – techniques being applied to shale gas reserves across the US. The same companies are now using the same techniques on shale oil reserves, with results that in many cases look as promising as the early stages of the shale gas revolution. US oil production is now on the rise, entirely because of shale oil production, as conventional sources such as Alaska or California are structurally declining, and as Gulf of Mexico production is poised for a post-Macondo recovery.

Doomsayers had reasonable grounds for suspecting this – but failed to address the bigger picture, one which includes technological innovation. They simply wanted Doomsday a little too badly. The briefing note continues:

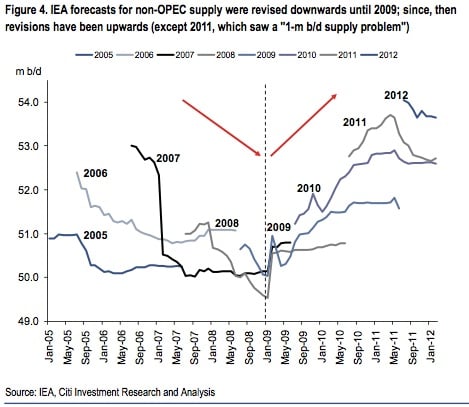

Belief in peak oil was bolstered by the repeated failure of supply to live up to the optimistic forecasts put forward by various governmental and international energy agencies. The IEA, the industry benchmark, made a habit of putting forth forecasts for the coming year of big gains in non-OPEC supply, only to spend the next 18 months revising those forecasts lower

Citigroup also castigates the oil industry and experts for failing to take this into account – over-promising and delivering late.

It’s a must read. Oil production is far more contingent on upstream investment than many people realise. When it does respond, it responds rapidly; the US well count has increased 500 per cent in three years.

So what now?

Yet Peak Oil isn’t the only casualty of recent energy developments. The death of Peak Oil kicks away the underpinnings from a great deal of policy-making by our bureaucracies and their advisers. Over the past two decades, we’ve seen the mushrooming of the “sustainability” sector, which is almost completely dependent on state funding and which shares similar erroneous assumptions.

The proposition we’re invited to accept in each case is that modern industrial society is founded on a resource which is being depleted and which cannot be easily replaced. The second part of that is rather crucial. Peak Oil thinking was based on the idea that crude oil couldn’t be replaced by unconventional oil and, in time, with synthetic hydrocarbons. We’re now seeing unconventional oil production ramp up, and in a decade the low-carbon synthetic replacements for oil will be in production, too, assuming oil remains at $40-$50 a barrel.

The deeper problem shared by both “sustainability” and “Peak Oil” thinking is that both camps insists on thinking of a resource not as a vector, but as a thing – a thing that’s rare, unique and irreplaceable.

The Victorians once depended on whale blubber for lighting and heating – and fretted, much like today’s sustainability crowd, about what might replace it. Human inventiveness rapidly provided an alternative. And policy-makers were once gripped by the constrained and volatile supply of saltpetre, the nitrate being essential to both feeding their populations and making things that went bang. Then chemistry came to the rescue. Of course a resource is a combination of things – the limits of human invention being just one.

This inflexibility in thinking is proving fatal.

Of course, simply because we are quite good at inventing stuff doesn’t mean utopia is imminent or that politics as usual will somehow be suspended. Future technologies will still be priced, rationed and abused. But it signals the beginning of the end of what we might call Apocalypse Politics – where unpopular and daft policies gain traction simply because their advocates claim that they’re justified by some catastrophic and irreversible historical trend.

Nobody but the superstitious can really believe that any more.

0 responses to “Peak Oil: RIP”