Baidu is renowned as China’s glittering internet success story, and as the start-up that gave Google a bloody nose. It dominates the web in the world’s second biggest economy with 70 per cent market share, and on Wall Street carries a market cap of almost $12bn.

But Baidu’s success comes at a price, for the legitimate music business, for the development of China and of its intellectual property (IP) law, and for any internet company wishing to do business in China.

Baidu owes its success to its MP3 Search service, which takes surfers directly to music. It’s known as “deep linking”, and early this year, sound recording owners represented by IFPI filed a copyright infringement case against Baidu, claiming damages worth $9m.

Yet the scale of Baidu’s operation, uncovered by a forensic six-month investigation conducted in China for The Register, has surprised the music business.

“Although we already had some doubts about Baidu mp3 search, when we saw the investigation results presented, it was really a shock,” Susanna Ng, EMI Music Publishing Managing Director, Asia Pacific told China’s Fortune Times.

Music searches using Baidu return results that are heavily skewed in favour of unlicensed music, while they rarely return search results for licensed music sites. Meanwhile, the unlicensed MP3s appear to systematically move around a complex network of domains in response to infringement notices.

Chinese web surfers may be forgiven for missing the news. Baidu fails to link to news stories critical of the company, including some of the findings below; these have been covered only by a handful of publications within China. It’s a chilling reminder of the ability of a web search engine to control and shape public discourse.

We’ll explain what Baidu does, and why it’s in trouble. And the grim prospects for anyone hoping to build an internet business in China — with an unstoppable Baidu.

What does Baidu do?

Most full-length recorded music in China is unlicensed, infringing material. Some estimates put the figure as high as 98 per cent. A popular act can expect to sell as few as 2,000 copies. Yet China is not quite the lawless frontier these figures suggest.

In March this year, another Chinese top five music search engine, Zhongsou had its servers seized and subjected to the maximum fine for copyright infringement by state administration authorities. This was the first public case of a music search engine being convicted for hosting MP3 files. Government appointed bodies such as the Music Copyright Society of China (MCSC) and the China Audio-Video Copyright Association (CAVCA) are both active in attempting to support businesses that reward the creators. Baidu’s notorious MP3 Search is the biggest problem they face.

MCSC’s Director of Legal Services Liu Ping used the following real life analogy to describe deep-linking:

“If Google’s search works as a guide by giving directions and telling you the address while taking you right to the door of your destination, Baidu’s search brings you directly through the door, right inside the room and helps you take away the CD from shelves without the owner’s permission.” Liu Ping considers this to be beyond the scope of a search engine, and a practice which moves Baidu into the area of transmission of music.

Baidu has amassed numerous lawsuits over the practice, with MCSC and the IFPI involved in a number of these. Baidu’s defence is that as a network service provider it cannot be responsible for the legality of the sites it indexes and is therefore not liable for damages. Nevertheless, Article 23 of China’s Copyright Law says that it is jointly liable “where it knows or has reasonable ground(s) to know” that the linked works are infringing material.

However, our investigation suggests close enough linkage between Baidu’s business and the infringing material for it to be viewed as something more than ‘just’ a network service provider.

Baidu’s MP3 Search was monitored for six months at the end of last year, analyzing search results using 600 songs spread across multiple genre. A number of areas that seemed incongruous to a pure and neutral search engine were discovered, and three details emerged.

Firstly, a network of mysterious sites with closely related domain names contributed more than 50 per cent of the search links returned by Baidu. The songs hosted on the mystery sites were unreachable except through the Baidu search engine. Furthermore, infringement notifications resulted in unlicensed songs simply moving from one of these domains to another.

Secondly, Baidu does not link to the two leading paid download sites in China, 9Sky and Top100. While Google for example will return results for a song search to licensed providers (7Digital, Amazon, eMusic or even iTunes) as well as Torrent trackers, Baidu is much more selective.

Thirdly, music blogs and forums naturally form a significant source of music search links for any search engine. But with Baidu, these contributed to only 30 per cent of the music search links on Baidu’s MP3 Search.

The cumulative effect is to keep the “free music flowing” for Baidu’s users — with devastating consequences not just for creators, but for rival internet businesses.

Closely related domains

Many of the domain names returned by Baidu MP3 Search lead to a single IP address. The series of domain names were formed by one letter + one numeral + 2 letters.

A typical example is the **yy.cn series of domain names which during the monitoring phase all pointed to the same IP address 219.153.42.69 — which was then later changed to the IP address 61.188.38.84.

The following are examples of this **yy.cn series

b8yy.cn c8yy.cn e8yy.cn f8yy.cn H8yy.cn i8yy.cn m1yy.cn m3yy.cn m5yy.cn M6yy.cn a8yy.cn k8yy.cn l8yy.cn n8yy.cn O8yy.cn p8yy.cn q8yy.cn r8yy.cn s8yy.cn U8yy.cn

The common feature of these domain names is that the homepage contains no information. The only access to music files is via a search engine.

For example, on one day late last year, two domain names hosting unlicensed MP3s, b8yy.cn and m1yy.cn, were leading to a single IP address.

Six weeks later, these had been joined by five more similar domains — h8yy.cn, m1yy.cn, m5yy. cn, m6yy.cn, b8yy.cn, c8yy.cn, f8yy.cn and iy8yy.cn. There were similar series of domains beyond just the **yy series.

Song Artist URL IP Address

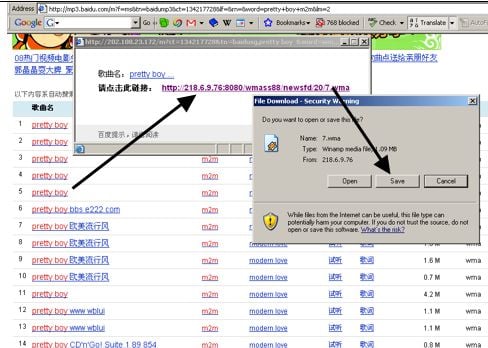

Pretty Boy M2M http://www.h8yy.cn/mv/010020021/0000/M2M-prettyBoy.654.wma 61.188.38.80

Pretty Boy M2M http://ting.b8yy.cn/wma/010020021/0000/M2M-prettyBoy.654.wma 61.188.38.80

Pretty Boy M2M http://mv.f8yy.cn/wma/010020021/0000/M2M-prettyBoy.654.wma 61.188.38.80

Pretty Boy M2M http://mv.h8yy.cn/532/010020021/0000/M2M-prettyBoy.654.wma 61.188.38.80

For these **yy series domain names, it is quite obvious that there are signs of human intervention in the way that the music files are moved around. As of now, the music has migrated away from the yy series and moved on to a new series, m*mus.cn.

But Baidu also affects the choices available to Chinese web surfers by choosing what they see.

Putting Baidu to the test

A search engine reflects the values and priorities of the engineers who design the algorithms. But not all search engine results pages (SERPS) are equal, as this example vividly demonstrates.

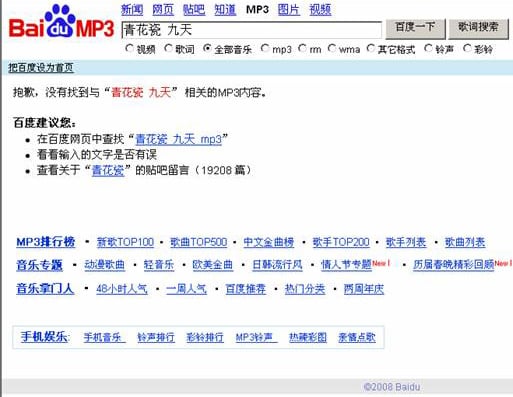

This picture shows the results returned for searching for Jay Chou’s song Blue and White Porcelain on Google China, with the key words of “Blue and White Porcelain 9Sky”, in Chinese. 9Sky is the name of the legal music store.

The following picture shows a result of a Google China search for the phrase “Blue and White Porcelain 9Sky”

Google China: legitimate sites and blogs rank highly

Google’s Search result for “Blue and White Porcelain 9Sky” (in Chinese) shows 9Sky as the first result.

Google directs users to the legitimate store, 9Sky

The same search phrase on Baidu’s MP3 Search draws a blank:

Baidu shuns legal music

Moving target

It’s a cat and mouse game fraught with difficulty for investigators. The Hebei Copyright Administration and legal authorities finally managed to pin down full liability on music search engine Zhongsou for hosting illegal music files on its servers. Zhongsou was offering a similar service to Baidu. Zhongsou’s network of domains was registered under false names of individuals, and it required laborious investigation to track down the servers. The Copyright Authorities and legal investigators then had to furnish the ISP with notarized proof of offence, before the server ownership details were revealed. And in the Zhongsou case, it required haste and secrecy to convince the ISP to not only to grant them access, but also the authority to seal the servers to prevent tampering or removal of evidence.

Because a Baidu MP3 search for a single song can show hundreds of URLs, monitoring is particularly difficult. Since songs hosted on the **yy.cn domains are regularly rotated, the infringing song will inevitably re-appear under another ****yy.cn** domain name and URL, and Baidu can claim that it has complied with the take-down notice without removing the offending sites from its search index.

Whoever the manipulator of these domain names turns out to be, the contents infringes PRC Copyright Law Article 47(1), and the hoster therefore bears direct and primary liability. Baidu’s decision not to index many songs on third party music blogs has a fortunate economic benefit for the company: it reduces Baidu’s administrative cost of policing infringement.

The net effect is that the MP3 song file in question is always available on Baidu’s MP3 search engine, despite any number of take-down notices by content owners, and Baidu’s MP3 search users are always gratified — keeping Baidu’s traffic flowing.

Baidu’s categorization of music links into genre categories and charts also takes it further away from the notion of a “neutral” search engine. In addition to MP3 Search, Baidu also provides the full infrastructure for users to organize music download links into new personalized albums which they can then share with other users via Zhang Men Ren, and music box personalized playlist services.

The money trail

Research houses, financial analysts and advertisers have paid little heed to the precarious foundations of Baidu’s success. The government body, the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), has said that “MP3 search is the primary boosting factor for Baidu’s high growth”. With the large number of users attracted to all this free music, users simply stay on and continue to use Baidu.

Baidu’s decision to trade its shares on NASDAQ was a conscious decision to distinguish itself from the scrabble of Chinese internet entrepreneurs. A New York stock listing brings legitimacy — as well as blue chip investment. In turn, this raises questions of due diligence: the JP Morgans are simply investing somebody else’s money.

Ironically, a significant portion of Baidu’s institutional shareholders and mutual fund investors are American companies, including blue chip investors such as US investment companies like Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan, Fidelity and Goldman Sachs. Leading Western brands like Motorola, Adidas, and Lancome have also profited by advertising on Baidu’s infringing activity. Both investors and advertisers seem oblivious to the misappropriation of musical assets while the money rolls in.

Has Baidu been entirely open with Wall Street? While Baidu’s regulatory filings in the US refer to its litigation with music companies, they don’t hint at the full extent of its music operation: or its precarious nature.

In its SEC filings, Baidu acknowledges that “a significant portion of our traffic is generated by users of our MP3 search service.” Baidu also refers to the “deep linking” lawsuits in China, and the threat to the entire business posed by having to close MP3 search.

“These results provide new data and suggest new insights into the extent of Baidu’s violation of copyright,” John Kennedy chief executive of the sound recording rights group IFPI, told us.

“Baidu is quite simply the biggest infringer of music copyrights in China, generating huge revenues by deliberately providing access to illegal music. It is as big a problem for China as it is for copyright holders. Baidu stands out as a champion of old-style copyright abuse just at the moment when China is intending to champion fair trade, respect for intellectual property and a new home-grown creative economy.”

We put the following questions to Baidu’s financial PR agency Ogilvy:

- Is management aware that that many MP3 files listed in MP3 Search are only available through Baidu?

- Is management aware that the movement of these files is co-ordinated in response to infringement requests to ensure they are always available to Baidu users?

- Is it official management policy to downgrade search results returning legal, licensed MP3 searches and MP3 files outside Baidu?

- Given the importance of this information in ongoing litigation — should this not be fully disclosed to investors?

Ogilvy has not responded.

Baidu reported total revenues of US$240m in 2007, a 108 per cent increase over the previous year, and revenues of $82m in Q1 of 2008, which showed another 108 per cent increase over the corresponding period in 2007. Q2 revenues announced last month show Baidu hitting US$100m in Q2, up 87 per cent year-on-year.

The web economy that isn’t

Defiance of creators’ rights in order to build up a web audience will sound familiar to Western readers. As it becomes apparent that the much vaunted “Web 2.0 economy” is failing to deliver sustainable, wealth-creating businesses, startups are increasingly turning to music, the surefire way of attracting “attention”, making the calculation that the obligation to pay creators is optional. It’s the same dynamic we’ve seen here, but on a giant scale.

IFPI sounded a confident note to us that the rights of musicians and budding music entrepreneurs will eventually be respected.

“I’m confident that the law will eventually catch up with Baidu,” said Kennedy, “with the company paying out huge compensation claims”.

IFPI takes some encouragement that pressure is building on Baidu from the indigenous Chinese music industry, and hopes US investors can take notice.

“[Investors] have good reason to question their association with a company that is not only cynically expanding its business on the back of copyright infringement, but which is also likely to be found liable for the massive damage it is causing,” he told us.

Yet recently, EMI announced it was withdrawing from China, selling its stake in EMI Taiwan, Typhoon and Hong Kong’s Gold Label Entertainment. The British music company had earlier closed offices in Thailand and Singapore and is reducing its business, but it is not a vote of confidence that the world’s biggest internet audience can be monetized.

Baidu has already effectively reduced the price of music in China to zero. Last week, Google China responded with a legal, fully licensed MP3 Search engine supported by advertising. Both streaming and song downloads (192kbps, no DRM) are free. (The site is at www.google.cn/music, but inaccessible outside China). Google’s partner for the service, Top100.cn, scrapped its own download service to make way for the new venture. Labels are skeptical.

In addition, a study just published by the MCPS-PRS Alliance into the Radiohead experiment suggested that free might not be enough. (See Millions chose torrents over Radiohead’s own site — survey). “Fans” flocked to the familiar P2P torrent trackers. Can rivals hope to change the habits of Baidu users now accustomed to an uninterrupted flow of unlicensed music?

The fate of the unloved music business in China today may seem remote here. But it begs the question: does economic activity from music have to be destroyed, just so Web 2.0 survives?

©Situation Publishing 2008.

0 responses to “Baidu: China’s nonstop music machine”