Engineers will rarely tell you something is impossible, even when your proposal is a very bad idea. Computer scientists at Stanford and MIT in the 1970s came up with a wonderful expression for this, an assignment that was technically feasible, but highly undesirable. They called it “kicking a dead whale down a beach”. The folklore compendium The Hacker’s Dictionary defines this as a “slow, difficult, and disgusting process”.

Engineers will rarely tell you something is impossible, even when your proposal is a very bad idea. Computer scientists at Stanford and MIT in the 1970s came up with a wonderful expression for this, an assignment that was technically feasible, but highly undesirable. They called it “kicking a dead whale down a beach”. The folklore compendium The Hacker’s Dictionary defines this as a “slow, difficult, and disgusting process”.

Yes, you can do it like that. But you really don’t want to.

In its efforts to show the world how keenly it is embracing CO2 emission targets, our Government has left a lot of dead whales on the beach for us, and as consumers, we’ll be the ones doing the kicking.

For example, it’s not impossible to heat a home with a heat pump, but it is a very noisy, ineffective and expensive way of doing it. An electric car might be fun to drive, but it is also expensive, and because of the inferior energy density of batteries, a petrol equivalent will always be lighter and go further. Nor at the end of the day will an EV be able to boast any CO2 emissions savings, we now know, thanks to Volvo. But perhaps the greatest whale to land on our beach is hydrogen.

Every day, manufacturers announce that they’re working on some kind of hydrogen initiative.

These include our best and brightest companies, such as Rolls-Royce and JCB. The Government has a Hydrogen Strategy. The Climate Change Committee thinks hydrogen is wonderful. You may think these are all signs that it’s a good idea. But things are not what they seem.

Hydrogen has two big problems which turn any project into a dead whale exercise.

The first is that pure hydrogen doesn’t exist – it’s both everywhere and nowhere. We must generate all the hydrogen we can then use, and this requires a lot of energy. This is fine when the output of the process is something very valuable to us, such as fertiliser. But less so when the output of the process must compete with much cheaper commodities, as it must in an energy market.

Secondly, hydrogen’s intrinsic physical properties create a whole range of unique problems. It’s a tiny atom that easily escapes confinement. Keeping it captive for storage is expensive, and moving it around safely even more so, because in liquid form it must be very cold.

Hydrogen advocates tend to shrug off these issues – solving them will be someone else’s problem, they reckon. Individually, none of these factors make hydrogen as an energy carrier or storer impossible, but the whale-like properties are becoming harder to ignore.

To replace gas boilers with hydrogen boilers requires thousands of miles of new, much thicker, high-pressure pipes. Last year, Lord Martin Callanan, the energy minister, candidly described the plans to replace our gas boilers with hydrogen boilers “as pretty much impossible”.

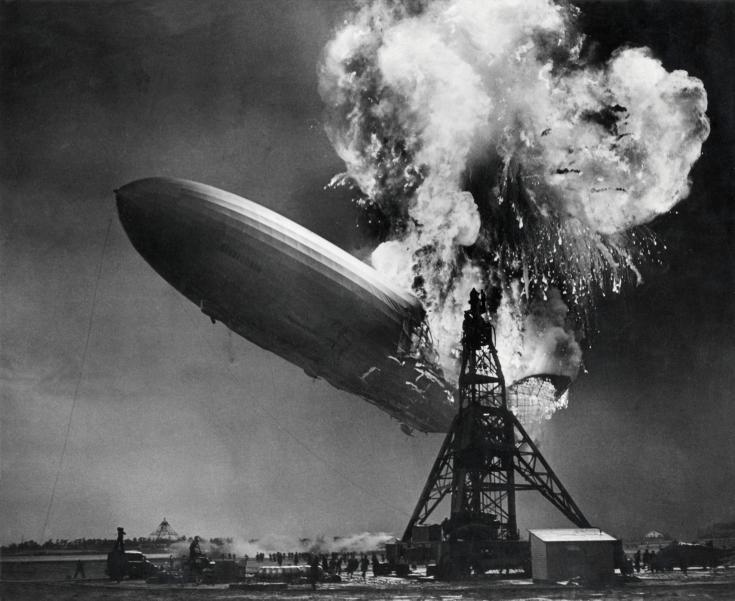

Wrong, m’Lud. It’s not impossible – it’s just a supremely bad idea. And when hydrogen explodes, it is quite spectacular. Right on cue, Australia’s first hydrogen carrying ship set sail for Japan this year, and burst into flames on its maiden voyage.

Again, hydrogen powered transport is not impossible, it’s just hampered by reality. Liquified hydrogen may be as light as petrol or kerosene, but keeping it at -257C requires much heavier apparatus. Converting a two engine turboprop from kerosene to hydrogen, I noted here recently, increases the weight of the engine from two tonnes to 13 tonnes.

As for storage, the story is little better. Wind often generates electricity when it is not needed (and doesn’t generate it when it is needed). So when the wind is blowing, the hydrogen lobby argues, we can create “green hydrogen” using electrolysis. These electrolysers are expensive, and sensitive, and switching them on intermittently to produce the mythical green hydrogen isn’t economic.

So green hydrogen is really not one, but two dead whales, engaged in a gruesome act of congress.

In his devastating assessment of the Government’s energy paper, Prof Dieter Helm calls it a “lobbyist’s utopia”. Prof Helm, an energy expert, describes how rent-seekers “[react] to each problem… by inventing another intervention. Each has unintended consequences, and these unintended consequences need more ‘fixes’”. That’s green hydrogen in a nutshell.

Green hydrogen may be generated reliably and cheaply using high-temperature gas-cooled nuclear reactors (HTGRs), a technology the Japanese have been refining for two decades. Japan’s first HTGR opened in 1997, but incredibly, was out of commission for a decade.

The history of nuclear energy is full of such stories, of untapped potential, and of avenues not explored. Our own Government tepidly hopes for a “HTGR demonstration by the early 2030s at the latest.” But even with a fleet of HTGRs generating hydrogen, the nasty stuff still needs to be stored and moved, and those costs haven’t gone away. Using hydrogen remains the worst way of doing almost anything.

Special interest groups however have discovered that the magic words “net zero” have the same incantatory power as “Open Sesame!”. In Arabian Nights, the phrase opened up a cave full of treasure. Here, they open up an unlimited trove of research grants and subsidies, and tap into abundant buckets of ill-directed “green” capital. The dead whale is never removed from the beach – and perhaps that’s the point.

This column first appeared in The Daily Telegraph.

0 responses to “Like kicking dead whales down a beach: understanding the Great Hydrogen Delusion”