Without anybody noticing, Opera has amassed one of the world’s most valuable commercial resources. And the funny thing is, it isn’t going to do anything evil with it. Marketing, new media and technology pundits may have to rethink a few things once they digest the size of Opera’s well-kept secret. It is possible the gurus may have spent years barking up the wrong tree.

At current growth rates, Opera will soon overtake Google as the owner of the largest transaction farm on the web. It is the Opera mobile web cache. Google currently handles 85 billion transactions a month. From 2008 to 2009 Opera grew from 21 billion to 36.9 billion. It is growing faster than Google, and at some point in the not-too-distant future, on current trends, Opera will overtake it. Users also spend more time in the Opera engine than the Google engine, which spits most people out to other destinations.

So what does Opera plan to do with this trove? First, let’s have a look how it came about.

Cache riches

Six years ago, two Opera engineers came up with a way of saving mobile operators money, by compressing web pages and sending them over slow, high-latency 2G cellular links in binary chunks. WAP had tried to do the same thing with WSP, but nowhere near as efficiently, and WAP required websites to created content in the WML format.

Opera’s insight was that CPU time on servers was cheap, but on a humble mobile phone, CPU and bandwidth were very expensive. A web page may need to talk to 20 other servers, and some of these need to talk to other servers. This bricolage then needs to be reassembled locally, a task that has increasingly taxed CPUs over the years. (A CSS file contains conflicting positioning information using several co-ordinate systems – these are resolved locally.)

Opera initially offered the technology as a caching proxy [1] to operators, called Mobile Accelerator. Then it decided to offer it directly to end users, via a new small lightweight browser [2] that talked directly to a proxy hosted by Opera itself. The Opera Mini client could run on all kinds of phones and its popularity grew and grew. Opera’s servers, which were originally in its downtown Oslo HQ, had to be moved outside, and soon became a major server operation. You can see it pictured here [3].

Now compare Google’s “transaction engine” with Opera’s “transaction engine”, and the Norwegian’s offering looks potentially very valuable indeed. Users spend far more time passing through the mobile cache than they do on Google. As well as searches, it contains destinations – news pages, social networking pages and emails. That’s what behavioural advertisers want. This wouldn’t be hard to do, and would involve injecting an advertisement into the binary stream that trickles into the Mini browser. But it’s also precisely what makes it a No Go zone for the company, says Opera.

Because its users trust Opera with such intimate information, the company feels it can’t engage in any Phorm-like behavioural exploitation. Break the bond of trust and they’ll destroy the business. Once upon a time, Google had a similar philosophy – Don’t Get Too Creepy Today (I may have mis-remembered that). Even Google does behavioural advertising now, but it’s very careful not to use the b-word [4].

In addition, Opera doesn’t feel it needs to. Opera has a few ideas on how it will make money in the future however, and some are evolutions of what it does today. So we’ll examine these for a second, before looking at what it’s got planned.

Auctions speak louder than (key)words

Today Opera’s income comes from three streams: licensing and royalties in one stream, income from active users and transactions in another stream, and “internet economy” income such as driving referrals to search engines as a third. The latter, by the way, is what keeps Mozilla afloat. So mobile networks pay to use Opera’s server technology because it saves them bandwidth, and improves the end-user experience.

Opera believes the future is transactional, which today amounts to less than 10 per cent of web advertising. So it’s sitting tight and waiting. It’s got an interesting trick up its sleeve, though.

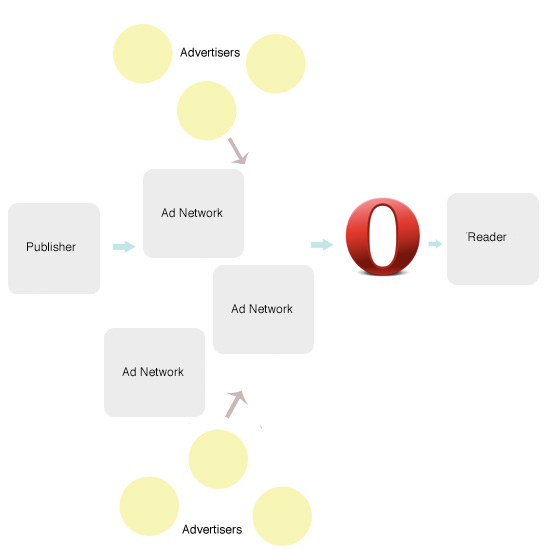

You might think of the pipe between Opera and the user as a private channel. It’s tempting to inject ads into that binary stream, behavioural or otherwise. Instead it’s doing something subtly different. Opera is going to allow advertisers to compete with other ad networks for ordinary web pages. In January, Opera acquired AdMarvel, which it maintains with its own brand [5]. AdMarvel has an unusual approach. It isn’t a conventional ad network, but rather performs arbitrage on competing ad networks, to allow advertisers to find the most effective properties for their ad spend. AdMarvel will swap out a Google advert for a rival ad network.

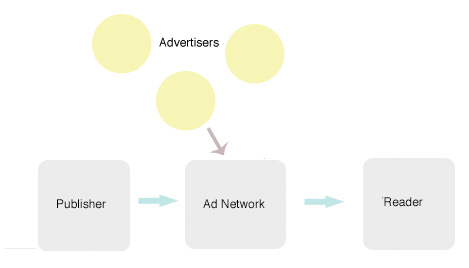

How it works today: advertisers bid on an ad network for keywords.

This puts it on a collision course with some of the most powerful forces on the web. Ad networks hate arbitrage, even though it’s a valuable market function that lowers the cost of advertising for ordinary people. Google all but bans it, periodically kicking out publishers who it suspects of the practice [6]. Google (and other ad networks) would rather you thought of them as “auctions”, which are ersatz substitutions for the pure market.

Opera introduces competition between ad networks for keywords

But we’ll never know the true value of a keyword on a given day, at a given time, unless the ad networks are made more transparent. It’s not a question of if, but when, the doors are blown off the keyword auctions. Whether it’s Opera that pushes the plunger remains to be seen.

The value of your cache

Critics might point out that Opera’s mobile web cache is restricted to certain markets – markets where mobile browsing is cheaper than landline internet access. When these mature, eventually landline will be cheaper, and the value of the cache will diminish. A similar argument is that once markets mature they buy “real” web browsers, such as the rich applications found on the iPhone and Android, and have less need for the mobile version.

There’s merit to both arguments. But it assumes Opera will stand still. Today, Opera Mini offers users a blazing fast experience on the iPhone that makes the native built-in web browser – which is excellent – feel painful. The fundamental technology reality is that it is cheaper to render on the server. For many instances this will continue to be true, provided that Opera continues to innovate and add value. Even on the fastest wireless network you can find – try loading a page on each, and then hit the back button.

I was hugely impressed with the patience and quiet, understated confidence of Opera on my visit. It reminded me of visiting Google 10 years ago, but without the self-conscious goofiness. And so it may not be in keeping with Opera’s heritage to pick a bloody fight with Google. Then again, it may succeed without having to. As we’ve seen with the EU browser ballot, Opera is a pretty tenacious fighter itself. ®

Links

- http://www.theregister.co.uk/2004/06/10/opera_mobile_accelerator/

- http://www.theregister.co.uk/2005/09/30/opera_strategy/

- http://www.digi.no/504306/her-kjores-egentlig-opera-mini&bid=3

- http://www.theregister.co.uk/2009/03/11/google_behavioral_advertising/

- http://www.admarvel.com/

- http://blog.searchenginewatch.com/070521-110658

0 responses to “Shhh… Opera holds the web’s most valuable secret”