Last year, the UK’s Cabinet Office asked an external management consultancy to examine staff morale and high turnover at the Government Digital Service. After interviewing more than 100 civil servants, its scathing confidential analysis described an organisation beset by low morale and run by a “cabal” management of old friends, who bypassed talent in favour of recruiting former associates – while Whitehall viewed GDS as “smug” and “arrogant”.

To the outside world, the Cabinet Office’s Government Digital Service is a kind of Disneyland, the theme park that when it opened, billed itself as “the happiest place on Earth”. GDS chief Mike Bracken CBE shared the secret of how to make a happy workplace with an American audience in 2013:

Hire the very finest minds in digital and dress them in onesies. Have some fun while you’re doing it. Insist on Hawaiian shirts – absolutely de rigueur. Make sure your insignia is good. And have lots of cake. And make sure there’s stickers. You can’t beat a few stickers for your laptop!

He continued: “These all seem like trivial things, but going against the tide, going against the grain, making sure that it’s a bit of fun, bringing this generation in, is utterly crucial. We started that literally on day one when we started.”

It was easily mocked as “infantile“. Yet Bracken’s thinking was pragmatic. As a new unit reporting to the Cabinet Office, GDS couldn’t hope to match private sector IT sector salaries. Contractors, or “interims”, could stay up to four years and received as much as £700 per day, but permanent staff would be on much lower rates. Hence the need for “fun” as a motivational tool.

Inside Aviation House, however, the reality was very different to the whimsical and informal picture GDS presented to the world. Three years after the Cabinet Office had approved Martha Lane-Fox’s blueprint for creating a new Whitehall IT unit, tangible progress was hard to find. The euphoria had given way to stress and high turnover.

“People were doubling up on leaving drinks because there were so many,” one government source familiar with GDS told us.

Morale had fallen so low that Cabinet Office management hired external management consultancy The Art of Work to find out why, and make recommendations. The consultants ran focus groups and conducted 1:1 interviews with over 170 civil servants. The final document, titled “Re-Designing GDS: People Proposition”, proposed nothing short of a “reboot” for the department. GDS needed to be “redesigned” with new management structures and processes.

The consultants’ report concluded that “high turnover makes it difficult to settle team/losing good people”. It also confirmed that GDS is perceived as arrogant in the rest of Whitehall:

“People needed to be reminded of professional behaviours; arrogance was the most used word to describe those inappropriate behaviours; also ‘smug elitists’”, civil servants told the interviewers, in confidence.

‘There are a high proportion of contractors, even for an agile organisation, which is not cost effective.’

Consultants highlighted a “culture of thinking we are always right”. GDS staff thought that the hype GDS generated for itself contributed to poor relations with the rest of Whitehall.

“I want comms to have humility so I’m not expected to be infallible or a member of a cult,” one protested to interviewers.

The HR experts also highlighted diversity issues, with a predominantly “mono culture” that was “male, white, geeky”, in the staff’s own words.

The most scathing findings are reserved for the top management, who GDS’ own staff say created a “chumocracy”. This would have consequences for morale, contributing to a high turnover of staff.

Staff described “shadowy cabals” of management, according to the report. This led to low morale and, ultimately, high staff turnover. The Cabinet Office convinced the Treasury and Francis Maude that it had recruited crack “digital experts”. In reality, GDS lacked experience, strong track records in delivering ambitious projects, and – as “digital” experts often do – lacked basic technology skills.

Cabal culture

It’s not unusual for a football manager to bring in his own back-room team. Yet it is unusual in Whitehall. GDS was exceptional in permitting its executives to draw quite so heavily on personal connections and old associations to fill the top ranks. It became a problem with GDS staff, the report found.

Of all the reasons the Art of Work report pinpointed for low morale and high turnover, this emerges as the clearest. GDS leaders were permitted to recruit who they wanted, and they recruited very narrowly into top positions. In turn, they excluded others from the decision-making.

The key personnel running GDS – chief executive Mike Bracken and deputy director Tom Loosemore – were “anointed” to lead the venture by Martha Lane-Fox, insiders say. Bracken had helped set up the NGO MySociety, where Loosemore was a director and treasurer. They also collaborated on TheyWorkForYou, and many of those volunteers would be appointed to senior positions at GDS.

Loosemore also drew on former BBC associates.

“Permanent staff progression was a problem if you were not in the Bracken/Loosemore fan club,” a source familiar with GDS explained. “Basically, you needed to come from a MySociety or BBC background, and be handpicked to get a good role”.

GDS staff told HR consultants that the nepotism was an important factor: staff felt career progression could only be achieved by leaving GDS.

“Reward is for the ‘chosen few’”, despaired one civil servant in the report. The consultants noted that:

The appointment of staff into new roles seems to frequently bypass any internal open competition, with roles going immediately to the external market or internal people being appointed by senior management on a basis of ‘who they know’. These practices have led to frustration for team members who feel they have missed opportunities.

It also noted:

There is a general feeling that you have to know the right people to get noticed, there is ‘favouritism’ and people do not hear about opportunities as they are frequently offered to external staff or new roles are filled by management without any ‘open’ competition.

Staff told external consultants that hiring old mates hampered career progression and created an insular organisation, convinced of its own brilliance, but unable to describe its purpose. As The Art of Work’s analysis found: “Because the majority of people are bought in at Band A, often at the top of this Band, there is no future salary progression.”

“There is a fine line between recruiting people you know are good, and making it a shoo-in for your mates,” one individual familiar with GDS told us.

Of the TheyWorkForYou volunteers, ten ended up as staff or contractors at GDS, with several taking senior positions.

Being favoured by the Bracken/Loosemore axis pushed out more talented IT staff, one Whitehall IT source familiar with its work told el Reg:

Most of the great stuff in GDS happened because really good people either took a big pay cut on the promise of great things to come or came in as contractors. Those that took the pay cut started leaving when progression was limited and the senior roles were already cornered by people like Neil Williams who got in there early.

The people that came in as contractors split into two camps: 1) the people that cared who have now mostly been cleared out, and 2) the people that are ‘delivery’ focused above all else, who have been kept on despite the damage they are causing.

“We’ve lost a lot of really, really good people who were contractors.

Conclusion

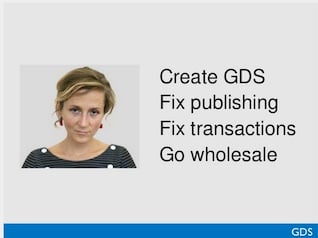

Slide by Tom Loosemore, Deputy Director GDS, 2013

Of the four goals, only the first can be said to have been achieved

GDS had four goals for government, according to its deputy director. It would “fix publishing” – by creating a single domain for government publications, rewriting content to make it more accessible and more widely used.

However, GOV.UK has been strongly criticised for confusing users and making government information less accessible. GDS’ own staff described transitions to GOV.UK as “a nightmare”.

GDS would also “fix transactions”, with Mike Bracken CBE promising that GDS would take 25 of the most-used “exemplar” services, and by March 2015 turn them into services “so good, people prefer to use them”.

“Government need outweighs user need every every time. And the way around that is by making sure the product is so useful and so beautiful it cannot be ignored,” Bracken told a US audience in 2013. [video]

The Labour Party pointed out that GDS had failed:

“The Cabinet Office has not hit its target of 25 exemplar services being live by March 2015, despite the budget of the Government Digital Service increasing from £9.7m in 2011/12 to £23.3m in 2013/2014. Spending by GDS on IT specialists has also notably increased in the last financial year, with a spend of £7.9m recorded in the latest data available,” Labour’s report (pdf) noted.

Only by “marking its own homework” did GDS turn alphas into betas, and betas into “finished” services, and then only hurriedly, after Labour pointed out it had missed its own target by a mile.

Today, few of the exemplars are truly operational or transformative. One, the “Digital Self Assessment exemplar”, is simply an email sign-up. Another, the digital front end to subsidy payments for farmers – touted by Bracken as a show-piece for GDS’ agile skills – has been scrapped, after its users reverted to paper and telephone en masse.

GDS furthermore promised that a new identity system would underpin UK government transactions with citizens, but it also failed to deliver this.

For now, both the Conservative and Labour parties continue to support the fourth GDS objective, “go wholesale”: become a software factory and box-ticker for regional public sector IT. This has been the focus of GDS strategy this year.

Our publication of the external consultants’ report into culture and management should make them assess whether GDS is fit for purpose in achieving this fourth ambition, of “government as a service”. Or whether, as some now openly argue, the same goal can be achieved much more cheaply by the use of industry standard tools, parts and practices – and without the box-tickers. ®

0 responses to “Special Report: Inside the Government Digital Service – the Happiest Place on Earth”